How Technology Change In Labor Of Productivity Is Measured

If yous read a lot of the business concern printing, you lot hear about how everything is just moving faster than we've e'er seen information technology earlier. Technology is changing the footstep of business concern, we're told, enabling companies to act and react faster than e'er. Every magazine, blog, and Twitter feed since 2012 has been warning that robots are coming for our jobs. To quote my young man North Dakotan, cultural commentator Chuck Klosterman, "Anybody knows that the Internet is changing our lives, mostly because someone in the media has uttered that exact phrase every single twenty-four hour period since 1993."

If you retrieve about your ain daily life, you lot tin can find a lot of plausibility for the notion that things are speeding up. After all, how often do you use a search engine such as Google—which is much more now than just a search engine, but as well an atlas, a shopping mall, a library, and a suite of part software, amongst other things? How ofttimes exercise you use social networks such as Facebook and Snapchat? How often do yous employ Grubhub or Amazon to perform transactions faster and more conveniently?

Recommended Reading

You tin can ponder all the time you spend on these things, and all the great things they do for you that you lot couldn't exercise xx years agone, and easily conclude that concern is speeding up. But if you look at the American economic system, things aren't speeding up for one important measure: productivity growth. In fact, by historical standards, productivity growth is pretty slow.

Y'all tin can think of all productivity measures as ratios of output to input. The most mutual one y'all hear near is labor productivity, or output per worker hour. This is the i that economists accept been following the longest, and we accept good confidence that we measure out it besides equally nosotros can. Information technology'southward besides where technological progress ought to show up: these new technologies ought to permit united states brand groovy new things without having to put new resources into the product of those things.

Making better things using the same amount of resource, or making the same things using fewer resources, is, in the end, where economic growth comes from. If this phenomenon is taking place, you should see it in the data reflected as productivity growth. The problem is, if you lot get look for it in the U.s.a., you don't find it. Productivity growth hasn't stopped altogether, only since the mid-2000s, the rate of growth has fallen considerably. Since then, the US has been averaging about ane.2 percent growth per year in productivity, but to understand that number, we need some historical context.

A brief history of productivity

There accept been four periods of broad productivity growth trends since the end of World War Two. We had a period of brisk labor-productivity growth in the start 25 postwar years, averaging 2.vii percentage per twelvemonth. In other words, for a quarter of a century, the value of production of every worker 60 minutes rose 2.7 percent per year. That means, in a sense, complimentary stuff: every yr, nosotros got 2.7 percent more things out of the same worker inputs than we got the year before.

And then there was a slowdown for twenty years, from 1974 to 1994, when productivity growth fell to 1.v percent per twelvemonth. This was a menses that included the rise of the personal figurer and the integration of new technologies in a number of industries, and as is the case today, people were wondering why productivity growth slowed down. In the belatedly 1980s, MIT's Robert Solow famously said, "I run into computers everywhere, except in the productivity statistics."

Eventually, we did see the computers in the productivity statistics. Around the mid-1990s, productivity accelerated once more, upward to about 3 pct per year. It stayed there for a decade earlier slowing downwardly once again. Information technology hasn't still picked back upwardly.

The productivity slowdown is indeed widespread: information technology'due south occurring in 29 of xxx countries in the Organization for Economic Co-functioning and Evolution.

Then the 1.ii percent average annual productivity growth we've been experiencing since the mid-2000s is less than half of what information technology was in the decade prior, and is slower even than the 20-twelvemonth slowdown from 1974 to 1994. Despite what seem like incredibly rapid changes in engineering, we don't see technologically driven growth in the data, and in fact we see the opposite pattern. Since economic growth requires productivity growth, if we don't figure out why this is happening and how to fix information technology, we won't get sustained increases in Gross domestic product per capita.

The slowdown I'yard describing might sound pocket-sized: i per centum or 1.v percent per twelvemonth doesn't seem like much. Merely if you compound that over multiple years, it really adds upwards. Suppose the slowdown afterward 2004 hadn't happened, and we kept going with the same average productivity growth that nosotros saw from 1995 to 2004. That would mean Gdp in 2017 would have been, conservatively speaking, $three trillion higher than it was. That's $nine,200 per capita.

That's roughly $nine,000 for every one of us, or $24,000 per household, that we exercise not take because productivity growth slowed down. Only a decadelong slowdown of 1.5 percent per yr adds upwards to real coin. If information technology continues for another 10 years, we volition exist missing a third of potential economic growth. In other words, Gross domestic product would be two-thirds of what information technology would be otherwise. You're talking near real differences in people'southward standard of living.

What's causing the slowdown?

So it'southward reasonable to ask, how can we have these great new technologies, yet they're not showing up in the productivity statistics? One reply is that possibly applied science isn't moving as fast equally we call up. If robots really were taking over our jobs, yous should see output per worker get way up—we'd have fewer workers considering robots would be making everything we were making earlier—but that's not happening.

Some people have said, "OK, that'due south non what's really going on. What's going on is nosotros don't measure out output very well." The thought is that what's lagging is non technological progress, but our power to mensurate it. New products or services aren't beingness captured in the way we measure out output, so productivity growth looks smaller than it actually is.

It'south non an implausible argument. To mensurate Gross domestic product output, nosotros look at total expenditures on all goods and services. But what exercise I spend when I take a picture on my phone? What exercise I spend when I go online and search on Google? Or while away a couple of hours on Facebook? I'm not paying annihilation. I'm presumably getting value from that good or service, but it'due south not showing up in the data. So some people debate that if nosotros could just measure the menstruum of fun people accept, or the enjoyment they receive from these products and services, it wouldn't show this slowdown that nosotros see in the statistics.

I tested this theory, which I call the mismeasurement hypothesis, in a recent study. The premise of the study is that even if we tin can't trust the productivity data, the mismeasurement hypothesis ought to have some implications about things we can measure, and then let'south look at these things and see what they tell united states of america. I did iv analyses to look at the question in unlike ways, and each fourth dimension, I found evidence that mismeasurement is non what's backside the apparent slowdown in productivity growth.

Comparing growth across economies

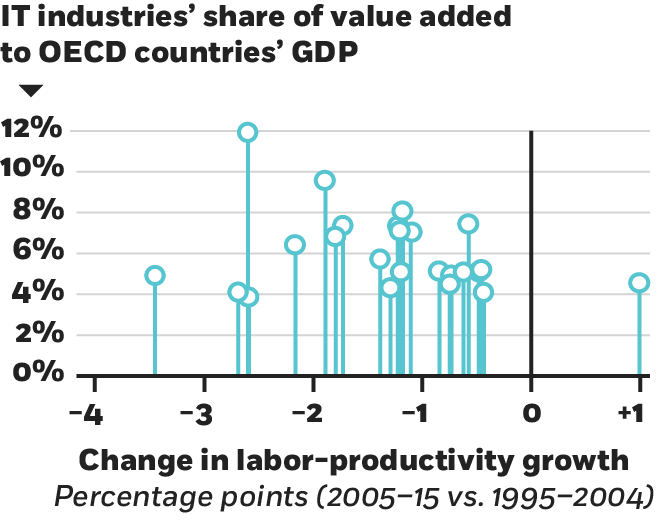

Commencement, let's await at whether this slowdown has happened exterior the United states, and moreover, whether the size of slowdowns across economies is related to the importance of data technology–related goods. The mismeasurement hypothesis implies that countries where Information technology stuff is more of import should have more mismeasurement, and so we ought to run across a bigger slowdown in these countries than in economies where tech is less important.

The productivity slowdown is indeed widespread: it's occurring in 29 of xxx countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-performance and Development, which is basically fabricated up of the wealthy economies of the globe. If you compare average productivity growth in the period 1995–2004 to the period after 2004, in all just one of those xxx cases, productivity growth is slower in the latter period. Productivity growth has likewise slowed in virtually of the emerging economies of the world—such equally Communist china, Brazil, and Russia—though for these countries information technology started a fleck after.

Syverson, 2017

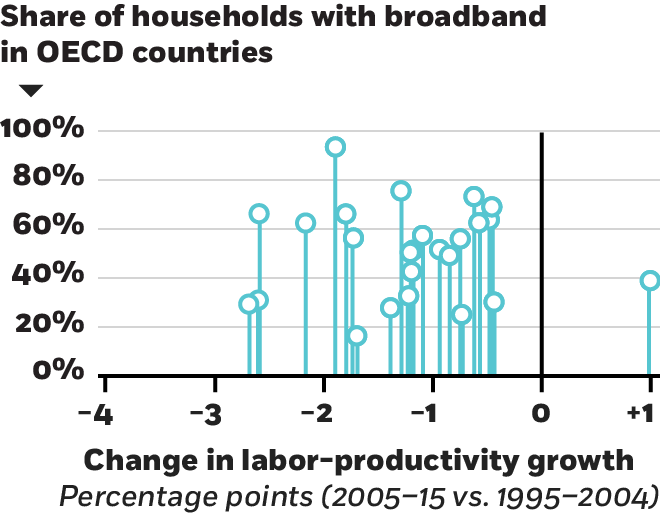

Is the size of the slowdown related to the importance of IT goods in these economies? Nosotros can gauge that importance using both supply-side and need-side measures. On the supply side, nosotros can look at the share of the country's Gross domestic product that is accounted for by product from Information technology-related industries. On the demand side, we can mensurate the importance of IT-related products using the broadband-penetration rate in the country in the mid- to tardily 2000s.

If nosotros compare the size of each country'southward slowdown to the importance of information-communication technologies in that country'southward economic system, as a share of total product, there is no relationship.

Syverson, 2017

Similarly, if y'all compare each state'due south productivity-growth slowdown to the fraction of households in that country with broadband admission, the human relationship is over again zero.

There just does non seem to be whatever systematic relationship between the size of the slowdown of productivity growth and the importance of Information technology products in a state's economy, which is a strike against the mismeasurement hypothesis.

Pricing IT

Next, permit's look at the work of other researchers who accept said, "Well, we've got a way to get at, through the side door, what the value of these technological goods are." We can take their methods, put in new data, and meet whether we tin get a feel for what the value of these It-related appurtenances might be. At that place are nigh a dozen or and so carefully done studies that attempt to put a value on technological goods, so do whatever of them arrive at a value anywhere almost $3 trillion?

In short, no. These studies typically produce figures in the neighborhood of $100 billion–$200 billion in the US. That'southward not pocket alter, but it's nix compared to the $three trillion of output that is missing because productivity growth has slowed. The highest estimate comes from Chicago Booth's Austan D. Goolsbee and Stanford'southward Peter J. Klenow, who calculate that the total consumer valuation for these products might be in the neighborhood of $850 billion. That's twice as large as the 2d-largest estimate, but still non fifty-fifty a third of the style to our missing $3 trillion. What'southward more, the studies to which I'm referring are estimating the total surplus created by these products—this includes revenues, which are used to summate Gross domestic product, but also consumer surplus, which isn't.

Implications of mismeasurement

Every bit a third analysis, let'southward accept the missing $three trillion at face value and say, "OK, permit's suppose that $iii trillion really does exist, and we just missed it in our statistics." What would that imply about what's happened if we did mensurate it? Let's wave our magic wand, say we're not missing that $3 trillion anymore, and so ask ourselves whether we believe those numbers one time nosotros've added that $three trillion back in.

According to what we can measure, IT-related industries in the US produced $1.4 trillion in total value added in 2015, the latest twelvemonth for which information are available. That's up from $800 billion (adjusted for aggrandizement) in 2004, so nosotros've had measured growth in the production of It-related products in the neighborhood of $600 billion. Now, if we take that these are the sectors from which this missing $iii trillion is coming, what we're really saying is that $600 billion is just the tip of the iceberg. In that location's another $3 trillion that was being produced merely that we missed in our statistics, and so the real number isn't $600 billion, simply rather $iii.vi trillion.

Then we can ask, "All right, do we discover information technology plausible that we have basically captured one-6th of the output that was really created in these sectors?" Is our ability to measure output and so poor that we really just capture about 17 percentage of the activity in these sectors? That'south the implication of the mismeasurement hypothesis.

Another implication is that productivity growth in these sectors was really astronomical. As measured, these industries experienced 80 percent labor-productivity growth. In 2015, a worker hour in these It-related sectors created lxxx percent more output than it did in 2004. That'due south very rapid growth. Simply co-ordinate to the mismeasurement hypothesis, it was actually much faster: 415 percentage growth over that 10-year period. Is it plausible that these sectors really experienced this sort of growth, which would be an order of magnitude across anything we've ever seen in whatever sector over an extended menses of time?

Another way to look at it is that $800 billion was most 8 percent of GDP when the productivity slowdown started. Three trillion dollars is 17 percent of GDP right at present. So are we missing 17 percent of GDP from a sector that accounted for 8 pct of Gross domestic product when the slowdown started?

I don't have empirical answers to whatever of these plausibility questions. But if aught else, nosotros can say that accepting the mismeasurement hypothesis would require us to swallow some hit figures.

The evidence of income

Finally, let's expect at income versus output. Gross domestic product is the total value of all expenditures in the economy. Gross domestic income is the income flip side of that. It's the total amount of income in the economy. These 2 things, when y'all add everything up, should be equal to 1 another, considering one person'southward expenditure is another person's income. But they never do in practice, considering they're measured using dissimilar data. The Bureau of Economic Analysis adds both measures upwards, and they're shut, but they're never the same.

If you lot wait at the gap between them, in that location'south actually a design to it. Since 2004, gross domestic income has been higher on average than GDP past nearly 0.5 percent per yr. If you add up all those differences beyond the decade, the decade covering the productivity slowdown, it adds up to almost $1 trillion. In some sense we're saying there's $1 trillion of income that has been earned over the last decade that isn't showing upwards in expenditures.

If productivity growth stays where it is, you should be worried. We are going to be considerably poorer than we would exist otherwise. Nosotros already are.

People have said, "Well, really, this gap is completely consequent with the mismeasurement hypothesis." The story is that companies such as Google, Snapchat, and Facebook pay people really well to create stuff that the companies and then become and give away for free. You see a lot of income, because the workers for these companies are getting paid, merely yous don't see expenditures, because no one's paying for Google when they employ it, and that'southward why you encounter this gap open upwardly. That's the story anyway.

The problem is, this gap did non open at the time of the productivity-growth slowdown. It opened up in 1998, and in fact, it was positive for every single yr between 1998 and 2004. The gap opened up not as we saw the rise of smartphones and social media; it already existed. Moreover, if you look at where the income growth has come from and why information technology's separated itself from output, information technology'due south come not from payments to labor, but payments to capital. In other words, profits are really loftier—precisely the opposite of what'due south suggested by the mismeasurement hypothesis and the accompanying notion of high wages combined with low revenues.

In role, this is because companies such as Google, Snapchat, and Facebook aren't just giving stuff away for gratis, of course. We may not pay directly for these services every time we utilise them, merely it's non correct to say that there is no transaction that'southward measured. For example, all the companies that advertise to me on Google, and Facebook and Snapchat, pay Google, Facebook, and Snapchat for that advertising. This is being measured in GDP. Moreover, I can't enjoy Google or Facebook, or use my GPS or photographic camera, until I purchase various devices, and I also tin't do whatever of that stuff until I get online by paying for broadband, wireless access, etc. All these transactions are part of Gross domestic product. It'due south non at all clear that we're not paying for any of this, or that we somehow don't measure out these payments.

All iv of these analyses imply that the productivity-growth slowdown is real. To suggest otherwise due to mismeasurement, y'all'd have to argue not that our measurement of output is bad, simply that it got systematically worse effectually 2004 or 2005, and worse in a particular direction. No one's been able to suggest this has happened.

Be afraid—merely don't panic

So how worried should you be? If productivity growth stays where it is, you lot should exist worried. We are going to be considerably poorer than nosotros would be otherwise. We already are. Ten years into the slowdown, we're each already $9,000 poorer per year.

Only in that location'southward reason to hope growth will pick support. Looking back through the historical data, I see our current growth tendency as an echo of past trends.

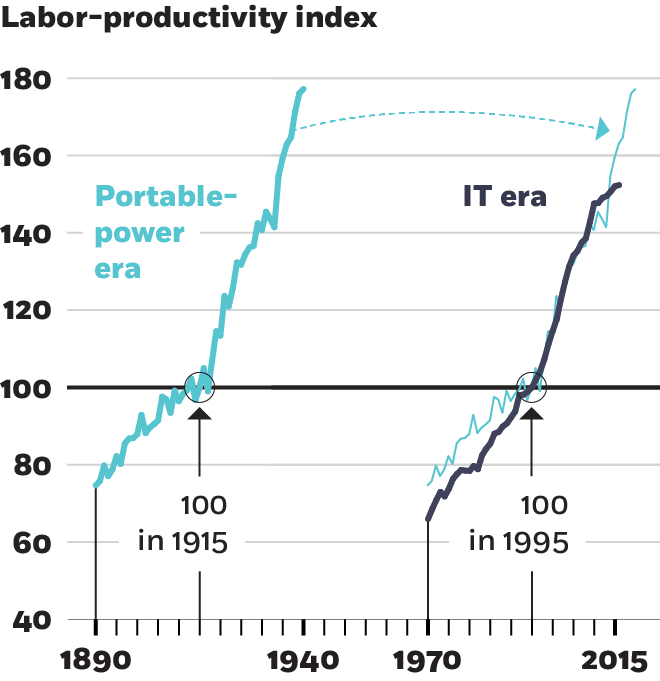

Historically, productivity gains from full general-purpose technologies accept come in waves. For instance, consider what I call the portable-ability era—the time of the diffusion of technologies such every bit the electric motor and the internal-combustion engine. This era starts around 1890 and ends in the mid-1930s. For the starting time 25 years of this era, productivity growth was quite wearisome: less than i.5 percent per year. Then starting around 1915, growth sped upwards to around iii percent per year and stayed in that location for a decade. Then things slowed again through the mid-1930s. So you have a 25-yr tiresome period while the technology was diffusing, a x-twelvemonth acceleration, and then another slowdown.

An echo of by productivity trends

An era starting around 1890, marked by the advent of the internal combustion engine and other technologies, saw periods of both quicker and slower productivity growth. A parallel tin can exist seen in more current times.

Syverson, 2017

Let'south compare this to the more recent experience of the It era, which began somewhere around 1970. Again, we had 25 years of slow productivity growth, a decadelong acceleration from 1995 to 2005, and then a slowdown. And then the question is, what happened after that 2d slowdown in the portable-power era? Well, there was some other acceleration, and productivity growth went dorsum up toward 3 pct a year.

We've had ane productivity growth moving ridge for Information technology, from 1995 to 2004. Nosotros may yet have some other. We may fifty-fifty take a third. That doesn't mean we definitely will have i, or that it's going to start tomorrow. Simply history tells the states that the productivity benefits of new technologies tin can come in multiple waves. It'due south almost inherent to the diffusion process of full general-purpose technologies that you have retrenchment periods during which people need to effigy out how to utilise those new technologies. The Information technology era is total of such technologies, such as artificial intelligence, that are just starting to find their place in commercial applications.

So have the productivity slowdown seriously, but don't despair of the future. Continue your eye on the information, and better however, brand yourself and your ain organization equally productive every bit possible, and let's all move the needle together if we tin.

Republic of chad Syverson is Eli B. and Harriet B. Williams Professor of Economics at Chicago Booth. This essay is adjusted from a lecture given at the Initiative on Global Markets' Myron Scholes Global Markets Forum in October 2017.

More than from Chicago Booth Review

More from Chicago Booth

Your Privacy

Nosotros desire to demonstrate our commitment to your privacy. Please review Chicago Booth's privacy notice, which provides information explaining how and why nosotros collect particular data when yous visit our website.

How Technology Change In Labor Of Productivity Is Measured,

Source: https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/why-hasnt-technology-sped-productivity

Posted by: hectorrusequithe.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Technology Change In Labor Of Productivity Is Measured"

Post a Comment